by Robert Chu

I had awakened from my afternoon nap. Grandfather was snoozing away in his peculiar method of inhaling through his nose and exhaling through his mouth, a little puff at the end of each exhalation. There was no television, no radio, so I decided to entertain myself with a plastic coffee can lid that I threw about the kitchen like a Frisbee. I threw it at the wall and watched it bounce off. Then I threw it at angles and watched it ricochet! I thought, in my 7-year old mind, “What would it be like if I had some real room?” I decided to go into the living room where grandfather was still napping away. “It’s pretty quiet, so I guess I can throw it and he’ll never notice,” I thought. I threw it and retrieved it once. No disturbance! “Wow! Look at it fly! Let’s try that again!”

The next thing I knew, Grandfather was awakened, furious! “Lao san (Number 3), why can’t you be quiet when I rest?!”

Uh, oh! I was in big trouble. I had awakened him from his nap! “You’re a mischievous boy and now I’m going to punish you!” He grabbed me by my collar and told me to squat in the corner in a peculiar stance for a half hour. I had no choice. Grandfather had decided and so there I remained, legs quivering, hands at my sides, panting and straining and sitting in the dreaded horse stance for the next 30 minutes, which seemed like an eternity. Grandfather grinned, “That’ll teach you to wake me up!”

Here I am now, some twenty-nine years later writing this article to tell you the benefit of that torture, er, I mean training. Whether you practice Hung Gar, Wing Chun, Tai Ji Quan, Northern Shaolin, Xing Yi or Ba Gua – there’s no getting around it! Whether you call it Zhan Zhuang (Pile Exercise), Jut Ma (Sitting on a Horse), standing meditation, or simply, stance training, it is the same. It’s a boring, strenuous exercise that even the advanced students want to avoid. But would you believe strenuous training is one of the quickest methods of developing internal power?

For the martial artist, one of the most important quests in learning and mastery of your art is the study of power (“jing” in Mandarin, “ging” in Cantonese, and often described as “internal power” in English). The most important thing in the quest for internal power is learning body connection for issuing that power. In my studies, body connection is the first way to developing power and sadly, too many practitioners are still searching for power after 20 years or so of practice. A student of mine, Kim Eng, once remarked that when he studied a so-called “internal art”, he was waiting to get the “qi power” after 20 years of practice. I laughed. I then gave him an understanding of body connection and One of the best ways to get power: stance training. This article will focus on Wing Chun kuen as it is the principle system I teach, and a few simple tests for the practice and development of stance and power.

The way I teach Wing Chun, the body structure and connection comes first. Later the forms solidify that training with the tools becoming involved. Partner exercises are introduced to be able to get used to utilizing this body structure in combat, and weapons skills are taught later to be able to project power with the body through a weapon. Personally, having seen many magazine articles and read many books, I first look at the demonstrator’s body to see if the can express power through their torso. Just a look at their pelvis and stance, and I can get a good idea if the martial artist is skilled or not. Quite often I am amused by the lack of body usage in their demonstrations of technique, even by advanced practitioners.

Power depends upon both internal and external factors. Oral tradition states, “Power originates from the heels, travels up the ankle and knee joints, is in conjunction with the waist, issues forth from the body and rib cage, travels down the shoulders, to the elbow, to the wrist and manifests from the hands”. A proper positioning of the body, muscle relaxation and contraction, breathing and timing are also factors involved in this.

Basic Alignment

Proper body structure comes from aligning the 3 dan tian and is crucial to the development of this power. You must align the Yin Tang (an acupuncture point between the two eyebrows), Tan Zhong (Ren 17, a point located on the midline of the body, level with the 4th intercostal space) and Qi Hai (ren 6, also known as dan tian, a point 1.5 cun below the navel) points in one line. (See illustrations). With this basic alignment in place, you can easily attain the “Qi feeling” in the body – that would be first what is called “Xiao Zhou Tian” (Small Microcosmic Orbit), then later advance to “Da Zhou Tian” (Big Microcosmic Orbit) which extends awareness of Qi flow throughout the body. As the focus of this article is more on the more physical aspects and benefits of body structure and stance training, I will discuss this more in detail in a future article or advise you to look for other qualified teachers in standing meditation.

Test # 1

With this basic posture aligned, you should try a simple test of alignment with the Yee Ji Kim Yeung Ma (Yee Character pinching goat horse), the basic stance practiced in Wing Chun. First, you should try to stand when a force or pressure is exerted upon you. For example, let’s say a person puts their palm on your chest and presses with continuous force. The pressure should not send you flying back, but should root you to the ground. You cannot develop this power if you are leaning backwards like the Leaning Tower of Pisa, or “hunchbacked” like Quasimodo of Notre Dame. You need to relax and sink and maintain the proper alignment in doing these tests. You equalize the pressure exerted by adjustmenting your balance and pushing forward with the pelvis. The buttocks and the quadriceps are brought into play and also help with this equalization. You should not be as limp as a noodle when relaxed, nor as rigid as a board. You have to have a Yin & Yang, a dynamic interplay of the soft and hard to be able to do this.

With this basic posture aligned, you should try a simple test of alignment with the Yee Ji Kim Yeung Ma (Yee Character pinching goat horse), the basic stance practiced in Wing Chun. First, you should try to stand when a force or pressure is exerted upon you. For example, let’s say a person puts their palm on your chest and presses with continuous force. The pressure should not send you flying back, but should root you to the ground. You cannot develop this power if you are leaning backwards like the Leaning Tower of Pisa, or “hunchbacked” like Quasimodo of Notre Dame. You need to relax and sink and maintain the proper alignment in doing these tests. You equalize the pressure exerted by adjustmenting your balance and pushing forward with the pelvis. The buttocks and the quadriceps are brought into play and also help with this equalization. You should not be as limp as a noodle when relaxed, nor as rigid as a board. You have to have a Yin & Yang, a dynamic interplay of the soft and hard to be able to do this.

This first test often upsets people who think that the basic stance is not a fighting stance at all, and not strong in the face of frontal force. What I write here is contrary to the majority of Wing Chun practitioners’s experience. Most who lean backwards or are hunch over like a patient sick with pulmonary emphysema will fail this test. Some will have practiced Wing Chun kuen for many years and not be able to pass this simple little test. I consider this a shame. The basic stance, Yee Ji Kim Yeung Ma, is practiced about fifty percent of the time in Wing Chun training. It is used throughout the first form, as the beginning and end of every section in the second and third form, the dummy set, and the knife techniques, and and forms the basis for many partner exercises as well.

Failing this test may suggest that your lineage is stressing form over function. My motto is “stress function over form and allow application to also be your sifu”. The benefit to learning something like this is that you can see if you are actually using power with your entire body, rather than from the limbs alone. The key here is using the pelvis and making sure that the buttocks is ahead of the heels.

Whether you are standing on both legs or one, the alignment remains constant. Again, if early and advanced Wing Chun training emphasizes this basic stance, and you cannot pass this test, you really should  seek some qualified instruction.

seek some qualified instruction.

In the beginning, I suggest that you stand in Yee Ji Kim Yeung Ma with hands held at the sides first. Later, you can do these tests with variations. Instead of pushing on the sternum, you can have hand postures of double Tan Sao position (Dispersing Arms, test one, variation 1), double Fuk Sao position (Subduing Arms, test one, variation 2), and double Gum Sao position (Pressing Arms, test one, variation 3). You can then test the structure by pushing on the arm position. With this, you can see if the arms are ideally connected with the torso. The idea is the feet grip the ground and support the legs, the legs support the knees, the knees support the thighs, the thighs transfer power to the pelvis, the pelvis to the waist, the waist to the torso and from the there, the torso connects to the shoulder. From the shoulder, the arms connect to the elbow, the elbow to the wrist, and finally to the hands. From controlling your intent and having awareness and sensitivity to adjust for changes, you should be able to easily have this feeling of being rooted.

Test #2

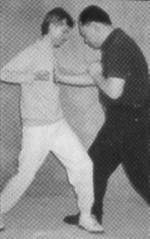

The second test is essentially the same as the first, however you should stand in a Bik Ma (forward stance, as illustrated), and allow your partner to exert the same pressure over your sternum. If you have the proper alignment and root, your rear foot will feel as though it is sinking into the ground. If you are striking someone, you will also have this feeling of pushing strongly into the ground with your rear foot. Since my method involves this stance with a 50/50 weight distribution, people who practice with a different emphasis with weight on their rear leg may find it difficult to pass this test. Those who do may want to investigate or discover why their lineage uses a stance in that way.

the same pressure over your sternum. If you have the proper alignment and root, your rear foot will feel as though it is sinking into the ground. If you are striking someone, you will also have this feeling of pushing strongly into the ground with your rear foot. Since my method involves this stance with a 50/50 weight distribution, people who practice with a different emphasis with weight on their rear leg may find it difficult to pass this test. Those who do may want to investigate or discover why their lineage uses a stance in that way.

Test #3

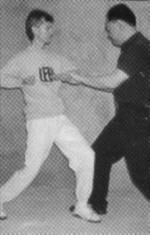

Following this, the third test also finds you in a Bik Ma and has your partner pulling your lead arm, now held in a Lan Sao (Obstruction Hand). If properly aligned, you will feel rooted

to the ground, with additional pressure on the lead leg. If you were in this stance/step, and you were pulling your opponent, you would also feel the lead foot strongly planted in the ground. For those who practice with weight emphasis on the rear leg, you now have your reasons why.

Test #4

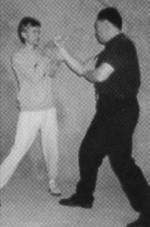

The fourth test has you in the Chum Kiu Ma, a turning stance also found in the second form. In the form, we typically use a Bong Sao (Wing Arms) from a straight facing position and have the weight distributed 50/50 in both legs. We test this by putting pressure on the Bong Sao and see is we can maintain the weight of our partner. If you failed test one, you probably cannot do this one. People who turn at a sharper angle may also find themselves unable to pass this test. The key, as before is to equalize pressure with the pelvis and maintain the torso in alignment. If your body structure looks like an “S” or “b” from the side (see illustrations), you probably do not have the body properly aligned.

distributed 50/50 in both legs. We test this by putting pressure on the Bong Sao and see is we can maintain the weight of our partner. If you failed test one, you probably cannot do this one. People who turn at a sharper angle may also find themselves unable to pass this test. The key, as before is to equalize pressure with the pelvis and maintain the torso in alignment. If your body structure looks like an “S” or “b” from the side (see illustrations), you probably do not have the body properly aligned.

The Purpose of Structure

My speaking of alignment in Wing Chun Kuen is similar to Xing Yi’s San Ti Shi (Trinity Stance), Tai Ji Quan’s Peng (bouyant / expansion) position and Ba Gua’s Niu Zhuan alignment (twisting power), as well as most forms of Zhan Zhuang (Standing Meditation) exercises. Wing Chun also follows this concept of alignment. Wing Chun’s oral traditions state, “Internally train a breath of air, externally train the sinew, bones and skin”. Yip Man was known to practice the Siu Nim Tao set (Little Idea, Wing Chun’s 1st form) for an hour. He was training to develop power.

I believe that power development comes to a student from day one in their training. It comes from the basics of stance, posture and relaxation. It’s just that beginner students are not coordinated, nor do they understand how to put things together, and it is often not explained why they do things a certain way. In my opinion, they are just doing things “externally”, simply mimicking a teacher’s motions without the understanding of why they are doing so. If a martial artist only emphasizes “purely external training”, they typically use weight training, stretching, and maintain an emphasis on endurance and speed. That’s fine, yet it does not tie into the rich concepts of complete body alignment, which is advanced training and provides a deeper understanding of one’s art.

coordinated, nor do they understand how to put things together, and it is often not explained why they do things a certain way. In my opinion, they are just doing things “externally”, simply mimicking a teacher’s motions without the understanding of why they are doing so. If a martial artist only emphasizes “purely external training”, they typically use weight training, stretching, and maintain an emphasis on endurance and speed. That’s fine, yet it does not tie into the rich concepts of complete body alignment, which is advanced training and provides a deeper understanding of one’s art.

One of my Wing Chun students, Gerry Pang, asked me while we had tea, “Sifu, does our art favor a larger person?” I asked why would he ask that? He said because he saw a majority of the students were bigger than him and they could make the art work. Then I told him that he must look at our core training, the core that emphasizes structure – turning it on and off, adjusting to the pressure and scientifically linking and unlinking the body at will. All of our forms emphasize structure, all of our partner exercises drill structure and all our weapons work supports it. I told him our art is designed for a smaller person to maximize his potential for power. Many teachers don’t emphasize that, so the body structure is emphasized when people are smaller than their opponent, not larger. I think he left our tea session satisfied with my answer.

My words do not only apply to Wing Chun here. They are universal for all systems of traditional Chinese martial arts. Many mimic the words “structure” and “alignment”, but without adequately testing their basic postures, they do not understand the depth of the meanings of these words.

Some may also think it is a waste of time to stand in these static postures. To be able to use power from the ground up is the epitome of all martial arts. I don’t think many emphasize the body alignment unless they, too, are looking to maximize the potential of issuing power. I have always studied other martial arts forms not for the sake of beauty or collecting systems, but for the sake of understanding their body connection concepts. Whether you be a practitioner of Hung Gar, Shaolin, Xing Yi, Tai Ji, Ba Gua, or Wing Chun Kuen, you should understand how to get power from your basic stance training.

Wing Chun people say “Yau, Shen, Ma Lik” (Waist, Body and Horse Power) and “Jang Dae Lik” (Elbow down power) to hint where the power comes from and how we should align ourselves. The Wing Chun Kuen Kuit (Fist Sayings) only hint how to develop power, however.

Conclusion

When you have developed one type of power very well, you begin to learn the variations of issuing power, and can manifest different forms of Ging (such as inch power, long power, and the like) by varying your timing and length of expenditure and direction of your power. You can only get this through training total body connection and coordination. If you do not have this form of training in your system, perhaps you can seek it out from other accomplished individuals in your system, or read the classics of your art, that may point the way. Perhaps my Grandfather found this as a form of “punishment”, but I was glad he gave me a head start in my journey in martial arts training and pointed the way for me to learn many great things.