Renowned for over a half-century in China, grandmaster Sum Nung (Cen Neng) has remained a well kept secret to most in the wing chun kuen family outside of the Bamboo Curtain. It is hoped that this article can help share with the reader grandmaster Sum Nung’s incredible legacy and his great contributions to the art of wing chun kuen.

Born in Peru, South America in May 1925, Sum Nung was brought to Foshan, Guangdong province, China by his father as a child so that their family name would continue in their native land. Originally from a well to do family, the Japanese occupation of the 1930s caused great hardship for the Sum’s, stripping them of much of their wealth and cutting them off from their relatives abroad. Eventually, to help support his family, Sum Nung took a job at Tin Hoi, a local restaurant in which his aunt was part owner. That is where it all began.

Due to his background, Sum Nung became a favored target for bullies. In order to defend himself, he developed an interest in martial arts. At first he tried to learn on his own by watching street performers, imitating their movements and conditioning methods. In 1938, however, when he was involved in a particularly violent encounter, his aunt asked the restaurant’s dim sum chef, Cheung Bo to take over Sum’s instruction.

Great Grandmaster Cheung Bo

Cheung Bo was born in April, 1899. He studied Hung ga kuen (reportedly from a monk) until an encounter with a wing chun kuen practitioner named Wai Yuk-Sang convinced him to switch over. Wai Yuk-Sang, a doctor with the Nationalist Army, was said to have been a grand-student of the famed Guangzhou marshal Fung Siu-Ching (a disciple of Red Junk Opera performer Painted Face Kam) who taught both medicine and martial arts in his spare time.

Cheung Bo had a fearsome reputation as a fighter. He taught wing chun kuen at the restaurant, at the Koi Yee Union, and from his home. In contrast to the types of wing chun kuen more widely seen today, Cheung Bo’s system did not make use of any boxing sets (kuen to, such as the siu lien tao or little first training). Instead, it was composed of separate forms (san sik), as well as a wooden dummy (muk yan jong) set, double-ended pole (seung tao gwun), and double knives (seung do).

Due to Cheung Bo’s large size and muscular frame, his wing chun kuen also differed in approach. Rather than keep his elbows closed on the meridian line (jee ng sin, an important point in the practice of other wing chun kuen boxers of the time), he used wider arms and compensated with quick and powerful facing and flanking methods.

Cheung Bo’s teaching methods were demanding and many found they could not last a long time under his tutelage but, seeing a great deal of determination in Sum Nung, Cheung knew he could give him a very solid foundation.

During workdays, Sum Nung would take every spare moment he could to practice, training his punches whenever his hands were free of the dim sum trays, and his forms whenever he found himself alone for a moment in the washroom. Even when he rested he would do so in a position that helped him stretch and better attain the demanding wing chun kuen postures. At night he would stay up past midnight to practice and wake up at dawn to continue.

Sum Nung’s dedication paid off and after a few years he learned all Cheung Bo had to teach.

More than just theory and training, even early on Sum Nung was forced to test his skills in real application. On one occasion, while he was carrying a heavily laden tray, Sum was attacked by a knife-wielding co-worker. Thinking quickly, Sum used the tray to block the attack and simultaneously kicked his opponent, sending the attacker flying across the kitchen.

On another occasion, Sum Nung was accosted by a man wielding double choppers–the large knives used to cut watermelons. While Cheung sat at a table a short distance away, Sum was forced to defend himself empty handed. As the deadly blades whipped by, Sum tried to protect himself as much as he could but received several nasty cuts along his arms. Luckily, he managed to find an opening and countered with lightning speed. Sum’s skillful response sent the man’s knives tumbling through the air, with one of the blades landing, point first, into the table in front of Cheung Bo.

Great Grandmaster Yuen Kay-San

Among Cheung Bo’s good friends at the time was Yuen Kay-San, the fifth son of the Zhenbei street fireworks merchant who was often referred to simply as Yuen the fifth (Yuen Lojia), who would often drop by to take tea at the restaurant.

Yuen Kay-San was born in 1889 and at a young age, his father arranged for him and his elder brother, Yuen Chai-Wan to study under the Foshan constable Fok Bo-Chuen (a disciple of Red Junk Opera martial lead actor Wong Wah-Bo and Painted Face Kam). From Fok, they learned the fist forms siu lien tao, chum kiu, (sinking bridge), and biu jee (darting fingers), as well as the wooden and bamboo dummy (juk jong), six-and-a-half point pole (luk dim boon gwun), and the double clamping yang slaying knives (yee jee kim yeung dit ming do), iron sand palm (tiet sa jeung) and other skills. When they had completed their lessons under Fok, the Yuen brothers invited Fung Siu-Ching, then just over seventy years of age, to retire at their home and followed him to learn close body (mai san) methods and advanced application until the old martial passed away at the age of seventy-three. Following Fung’s passing, the Yuen brothers went their separate ways. In roughly 1936, Yuen Chai-Wan moved to Vietnam while Yuen Kay-San stayed in Foshan and spent his time systematically analyzing his wing chun kuen, going on to became one of the first to organize and record its principles.

When Yuen Kay-San visited the restaurant, he often got a chance to see Cheung Bo’s students practicing and over time, came to admire the work ethic of Sum Nung. Eventually, seeing his friend’s interest and knowing he had already imparted as much as he could, Cheung Bo arranged for Sum Nung to continue his training under Yuen Kay-San.

Sum Nung was hesitant at first. He had been learning from Cheung Bo for a few years and saw Yuen Kay-San, older and thinner, as a stark contrast to his powerful looking teacher. This feeling led him to question Yuen’s skills. Yuen, however, seeing in Sum Nung a great desire and potential, was willing to indulge the youth. Promising that the youth could use all that he knew, and vowing only to defend in return, Yuen Kay-San invited Sum Nung to touch hands with him.

Sum Nung, his curiosity piqued, took up Yuen’s challenge. Sum attacked with all his vigor and the full range of his skills, but each time Yuen Kay-San calmly intercepted his techniques and after only one or two movements left Sum off balance, out of position, and unable to continue. Realizing that Yuen’s skills were of the highest level, Sum quickly became his student.

Fighting Spirit

Yuen Kay-San wanted to ensure he gave Sum Nung as encompassing an education as possible. In addition to one-on-one and group fighting, Chinese medicine, Chinese literature, and other pursuits, Yuen sought to give Sum confidence and a fighting spirit. Towards this end, he set up some public demonstrations for Sum and also some friendly tests of skill.

The first such test Sum Nung faced was against a famed local practitioner of one of Southern China’s “long bridge and big horse” (cheung kiu dai ma) systems. A stark contrast to wing chun kuen, Yuen felt it an important step in Sum’s training. The encounter was set to take place on a local rooftop. When the fight began, and the powerful roundhouse of his opponent came hurtling towards him, Sum Nung stood his ground, dissolved the attack, and promptly swept his adversary, knocking him into the roof-top’s railing wall and sending a few dislodged bricks clattering down to the street below. This led Sum Nung to realize that wing chun kuen was useful against a broad spectrum of other arts.

To further this idea, Yuen Kay-San next set Sum Nung up to face a well-known local wrestler. This opponent proved wilier and instead of attacking directly, he sought to fake out Sum Nung with feints. When their bridges finally touched, Sum was initially in a disadvantageous position and his opponent moved quickly to tackle him. Sum’s reflexes took over, however, and he cleared the wrestler’s grappling attempt and at the same time struck the man in the flank, sending him to the ground.

Sum Nung also had the chance to gain experience through touching hands with friends and peers. One man, much bigger and stronger, tried to use brute force to reach his flank but Sum changed quickly, gaining the advantage, and letting him fall to the floor. On another occasion, when a man told him he didn’t believe wing chun should contain any throwing movements, Sum made use of the wrapping arm from the chum kiu set to flip the man up and over onto his head. Yet a third time, on the restaurant rooftop where he worked, a man tried to use of a hard slapping movement to shock Sum’s forearm, but Sum reacted instantly by going with the force and leaking around it.

These and other encounters, in addition to making Sum Nung very grateful for having the fortune of studying under Yuen Kay-San, helped cement concept and application, forging him into a well-rounded, effective, and experienced martial artist.

Beginning his Career

By 1943, Sum Nung had made much progress and his reputation had grown to the point where people sought him out for lessons. This led to him accepting a few students whom he taught out of the Deep Village Temple. Among those early students was his uncle, Sum Jee who had previously been a well-known Hung boxer. He quickly gained other students as well, all experienced martial artists, many of whom were much older than he, attracted by the quality of his skill. Hard working and willing to test their knowledge, Sum Nung’s early students made his reputation for teaching as solid as it already was for fighting.

Alongside his wing chun kuen training, Sum Nung had also followed Cheung Bo’s teacher, Dr. Wai Yuk-Sang, in the study of osteopathy (ditda) and breathing exercises (heigung/qigong). Late in life, Wai Yuk-Sang experienced a profound spiritual change and became a Taoist priest. Deeply regretting that he had taught the martial arts, and thinking that someday his teachings, as they were passed down and spread to succeeding generations, may be used to harm or even kill someone, he wanted to make amend. With that in mind he taught Sum Nung the kidney breathing returns to source (sun hei gwai yuen) exercise and instructed him to perform it both before and after training, so that the martial arts would always be surrounded by the healing arts.

Moving to Guangzhou

Around 1945, with his devotion to wing chun kuen and medicine leaving him little time for restaurant work, Sum Nung decided to move to the nearby provincial capitol of Guangzhou to establish his medical practice. In the beginning, to help make ends meet, he taught wing chun kuen to members of local Iron and Five-Metal Workers Unions. When teaching his early students, Sum Nung

organized some of the separate techniques (san sao) that he had learned from both Cheung Bo and Yuen Kay-San, into the twelve separate forms (sup yee san sik), which included sections such as meridian punch (jee ng choi), single dragon punch (duk lung choi), inside outside yin yang palm (loi lim yum yeung jeung), flapping wing palm (pok yik jeung), and white crane catches the fox (bak hok kum wu), among others.

In Guangzhou, like in Foshan before, his encounters with other local practitioners helped grow his reputation and attract more and more students. Due to friction between the different guilds, many of which employed martial artists to teach their members, fighting became regular and eventually, hundreds became involved in almost weekly challenge matches at the nearby mountain. This, and concerns over wing chun kuen’s effectiveness in countering the seizing and holding techniques (fan kum na/ fan qin na) of the police lead to the local government’s banning of the teaching of wing chun kuen in the city.

In the mid-1950s Sum Nung made a short trip to Hong Kong to teach a seminar for the Fruit Market Union. Over a hundred people attended and the seminar was quite successful, especially his demonstrations of the counter kicking and fast throwing techniques of wing chun kuen. Despite requests to continue teaching by the union members, offers of partnership from other instructors, and warnings from old friends that China was getting ready to close its borders, Sum Nung was eager to get back to his family and thus returned to Guangzhou. Originally, he had intended to journey again to Hong Kong but before that could become reality, his friend’s warning came true and the borders were closed.

Sum Nung continued to travel back and forth to Foshan on the weekends to visit Cheung Bo and train under Yuen Kay-San until they both passed away in 1956.

Iron-Arms

Sum Nung was sometimes referred to by the nickname Tiet Bei (Iron Arms) Nung due to the explosive short power he could generate from his forearms with techniques such as the barring arm and center-cleaving arm. One encounter that helped fuel the nickname occurred during the Cultural Revolution. In those days, Communist China did not support the traditional martial arts and many practitioners were harassed, persecuted, and sometimes even killed. It was under these conditions that grandmaster Sum Nung was reportedly set upon one day by a gang of fanatics. In the course of defending himself, Sum Nung broke the arm of one of his attackers with a penetrating barring arm technique and managed to emerge unscathed. Shortly thereafter, Sum Nung was riding his motorcycle one day when he was cut off by a truck. When he confronted the driver, a knife-wielding compatriot attacked him from the side. Sum managed to deflect most of the attack with a half-dispersing-half-wing technique, but the blade was sufficiently long that it still stabbed slightly into his chest. Knowing that hesitation could prove fatal, Sum quickly threw his assailant to the side and simultaneously struck out with a tiger tail kick to the man’s ribs. The attacker limped away, badly injured from the devastating strike.

Other encounters lead to Sum Nung also establishing his reputation among the new, government schooled, martial arts experts. Another provincial wrestling champion, seeking something to bridge the gap between his long boxing and his Chinese (sut gao/shuaijiao) and Greco-Roman wrestling came to Sum Nung and proclaimed he could take Sum’s punch and then tackle him to the ground. Sum invited him to try and when the man came in, Sum flanked him and used a spiraling wing arm (bong sao) movement to knock him down. The man quickly became Sum’s student.

Guangzhou (Canton) Wing Chun

During the turbulent times of the Cultural Revolution, grandmaster Sum Nung continued to teach wing chun kuen but did so only privately, not wanting to attract attention. When some of his students moved to Hong Kong in the late-1960s and early-70s, they used the name Guangzhou Wing Chun Kuen to both distinguish their branch and to maintain the privacy of grandmaster Sum Nung, still in the Mainland.

Expanding the Art

Over the years, teaching only those whom he felt were upright and trustworthy, grandmaster Sum Nung went on to train many outstanding students (with apologies, far too many to list here). In addition to Sum Jee, Sum Nung’s students from the late 1940s to early 1960s included Ma Yiu-Moon, former dragon-shape boxer Lao Lo-Wai, former Ngok family boxer Ngok Jin-Fun, Pang Chao, and Leung King-Chiu (know as Dai Chiu, who moved to Hong Kong around 1970 and later to the United States).

From the mid-1960s, his students included the late Dong Chuen-Kam, Ngo Lui-Kay (who relocated to Canada in 1982), Kwok Wan-Ping (Fu family internal boxer who established the Guangzhou Wing Chun Taiji Institute in Hong Kong in the late 1960s), Lee Chi-Yiu (who moved to Hong Kong in the early 1970s), and Wong Wah (Tom Wong, who relocated to Los Angeles). Others also adapted his methods and spread them throughout the Pearl River Delta and as far as South East Asia.

Sum Nung has also endeavored to help keep wing chun kuen “in the family.” Honoring a pledge he made his first teacher, Sum Nung taught Cheung Bo’s seventh son, known as Ah Chut. Following Cheung Bo’s passing, those students wishing to continue their training followed Sum Nung either directly or through Ah Chut. Sum Nung and his students have also shared their insights with Yuen Kay-San’s grandson, Jo-Tong, who has written considerably on the art Martial World (Wulin), New Martial Hero (San Mo Hop) and other periodicals. In addition, Sum Nung is passing along the art to his own family, including his son, Sum Dek.

Sum Nung’s Legacy

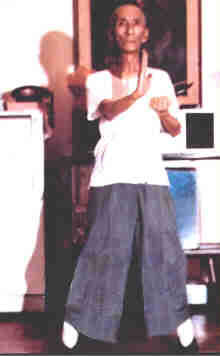

Grandmaster Sum Nung has continued to develop and refine his art over the decades, concentrating on practical application. So great and lengthy have his contributions been, many of his followers around the world have begun calling their art Sum Nung Wing Chun Kuen, in his honor.

Originally published in Inside Kung Fu

Sil Lim Tau, sometimes referred to as Siu Nim Tao, is the first of the hand forms of Wing Chun Kung Fu. It teaches the student the basics of the martial art. The form has been adapted and changed over the last few hundred years, but it is thought that the form was inspired by movements from both crane style kung fu and snake style kung fu. The form has evolved differently as styles of Wing Chun diverged. The snake element can be seen more in Yuen Kay San Wing Chun in Foshan, China, than it can in Ip Man’s Wing Chun which was reordered by Ip Man and his predecessors in Foshan and later in Hong Kong.

Sil Lim Tau, sometimes referred to as Siu Nim Tao, is the first of the hand forms of Wing Chun Kung Fu. It teaches the student the basics of the martial art. The form has been adapted and changed over the last few hundred years, but it is thought that the form was inspired by movements from both crane style kung fu and snake style kung fu. The form has evolved differently as styles of Wing Chun diverged. The snake element can be seen more in Yuen Kay San Wing Chun in Foshan, China, than it can in Ip Man’s Wing Chun which was reordered by Ip Man and his predecessors in Foshan and later in Hong Kong. The first section is for training the basic power by tensing and relaxing the arm. The strength is built up by repeating the core hand positions of Tan Sau, Fook Sau, and Wu Sau. If you wish to perform well in Wing Chun, you must use the first sections of Sil Lim Tao to train the basic power and strength. There is no short cut, once the movements of the form have been learned, they must be practiced seriously to train the power and strength. Every Wing Chun practitioner knows when practicing the first part of Sil Lim Tao, that it has to be slow. To train for the strength one has to be serious, and to be serious one must do it slowly.

The first section is for training the basic power by tensing and relaxing the arm. The strength is built up by repeating the core hand positions of Tan Sau, Fook Sau, and Wu Sau. If you wish to perform well in Wing Chun, you must use the first sections of Sil Lim Tao to train the basic power and strength. There is no short cut, once the movements of the form have been learned, they must be practiced seriously to train the power and strength. Every Wing Chun practitioner knows when practicing the first part of Sil Lim Tao, that it has to be slow. To train for the strength one has to be serious, and to be serious one must do it slowly.