by Hawkins Cheung

Learn to Think Like a True Fighter

As told to author, Robert Chu, in “Inside Kung-F

u” September, 1991

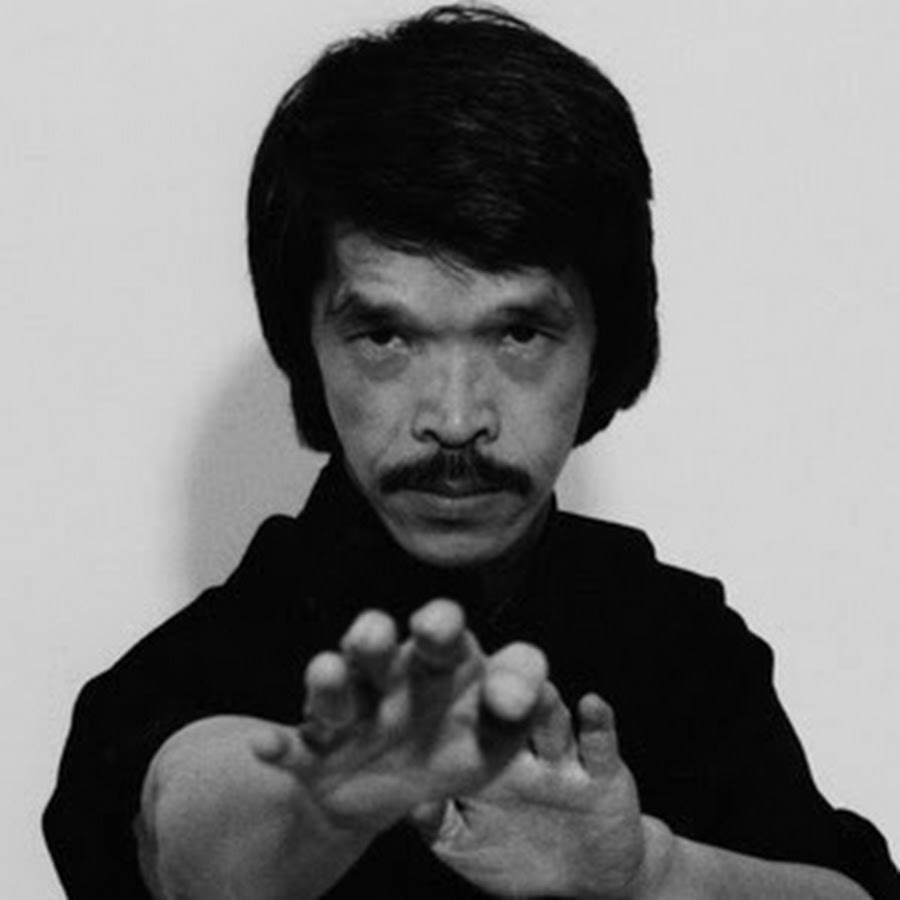

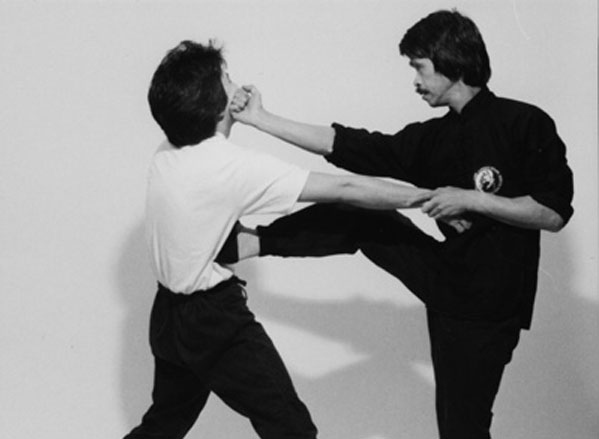

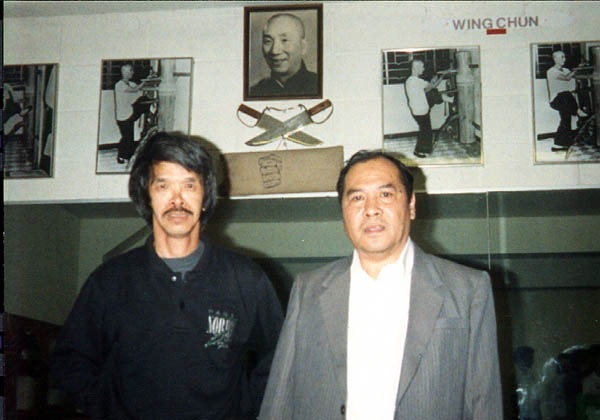

Many have heard of the wing chun system of martial arts. Most articles deal with the techniques, the chi sao, the forms, the politics, and the variations, but I believe this may be the first article that deals with the wing chun mind. Master Hawkins Cheung, who has taught in Los Angeles since the late 1970s, outlines the concepts of wing chun in combat. An early student of grandmaster Yip Man, Cheung has practiced wing chun for over 30 years. Hawkins was also Bruce Lee’s training partner in the early 1950s and together they explored fighting concepts. Master Cheung stands 5-feet-5 and weighs 105 pounds. He is every inch a skilled fighter and excellent teacher.

Cheung explains the wing chun mind and the “how” and “why” of wing chun. He also explains where many wing chun men are incorrect Cheung states that the principles discussed here could be used by any system of martial arts to be applied in combat, regardless of the tools delivered. He considers stylistic differences, postures, techniques, forms and drills secondary to wing chun’s application in combat. Master Cheung’s advice here is reminiscent of Sun Tzu’s Art of War. He offers practical, straight forward advice on combat, very much like his style of fighting.

Combat

Wing chun is designed as a combat system. For this reason, the system emphasizes confidence, timing, interc

epting, capturing the centerline, shocking the opponent, setting up for consecutive strikes, and trapping. But the most important weapon in wing chun is the mind. Cheung explains that the mind is the center, the “referee” that the system revolves upon. Cheung uses the term “referee” because it denotes a bystander, one who is emotionally detached. Cheung states that, “Having a calm mind will determine your success in combat” To Hawkins Cheung, the wing chun mind is the mental frame of mind you need to survive.

Confidence

Hawkins often uses an analogy of driving a car to convey his teachings. He asks, “Are you good driver?” A student nods affirmative. Are you a good driver in Europe? Are you a good driver with a manual transmission? Are you a good driver in New York?” The student looks confused, as Hawkins continues, “The difference between driving a car around the block versus driving a car on the freeway is confidence and experience. Confidence and experience go hand-in-hand. If you’re not confident, you will be a disaster in driving or fighting.” The students understand.

“Practicing with a partner develops confidence so that when you eventually face an opponent it will be like driving to the supermarket If you have fear, you will lose. Don’t fight it if you have too much to lose. If you must fight, you must destroy your opponent and not stop until he is defeated. You must have the fighting spirit and attend to the job on hand. Don’t have fear, let your fighting instinct guide you in destroying your opponent. This is the kind of confidence you need to face your opponent,” says Cheung.

“The basic drills pak sao (slapping hands), lop da (grabbing and striking) and dan chi sao (single sticking hands) give a beginning student a sense of facing an opponent. The first form, siu nim tao, advises the student to ‘not think too much,’ and gives the basic tools and how to utilize them, as in learning to drive a car, which you eventually do without having to think.” says Hawkins, “The wing chun system was designed to develop a person with no knowledge of martial art to eventually become a proficient fighter.”

“If you’re facing an opponent, you must have the confidence to walk straight in on his punch or kick! “exclaims Cheung. “There is no retreating step in wing chun; the idea is you have to ‘eat up’ your opponent’s space and step in. It’s not wing chun if you take a sidestep or retreat from an attack.”

Newton’s laws of physics states that only one body can occupy a space at a time. “You must rush in with absolute confidence. “Master Cheung states that knowing this is an important factor in mastering wing chun, “because if a practitioner can’t fulfill this requirement, he may as well study another style.”

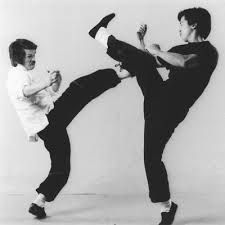

Timing and intercepting– “Can you do it?”

Hawkins often states anyone can learn the entire wing chun system in a short time, but it difficult to master. He often asks his students, “You can learn so and so, but can you do it?” Being a close-range art, wing chun is based largely upon timing. “Hitting a person just as he is attacking requires perfect timing:’ The question is, can you do it?” He notes many other martial arts styles are fast “The boxing jab is perhaps the fastest punch, and coming in on it is dangerous. By utilizing the proper timing, you can score a blow just as the jab is retracting or about to be launched.”

Timing is the prelude to intercepting or cutting off an attacking Says Cheung, “Fighting is based on shocking attack. To shock the opponent with a blow or through surprise will slow or stop his attack” Hawkins’ explanation is reminiscent of the German blitzkrieg (lightning) attacks of World Warn, and of the recent Persian Gulf War, where the Allied forces bombed Iraq through a surprise night attack.

Sifu Cheung continues, “You have basically two methods of capturing the centerline:

the first is to have superior speed over the opponent, and the second is start entering just as the opponent attacks. The key determining factor is timing.”

Cheung states if there is no starting point, a wing chun man will not initiate his attack “if you move, I move; but I arrive first”‘ says Cheung. Sun Tzu’s Art of War states that you attack after, but arrive first.

“Having a fight is like arguing with someone. When you’re engaged in an argument, you and your adversary are emotionally charged and each side wants to speak his point of view. But in wing chun, the idea is to let my opponent speak first, and I will initiate my timing from his start.” Cheung continues, “From that point, I shock or scare my opponent and initiate my say-so.”

Like a gunslinger, Cheung states that a wing chun practitioner has to develop the fastest draw. “A wing chun player captures the centerline first, which means he has the opponent targeted. if I am pointing my gun at you, and you move, even slightly, I’ll shoot Other Systems want to shoot as soon as possible, but with wing chun, you want to be the one that draws first, then shoot if necessary. “if you can strike your opponent at his moment of entry, the results can be devastating,” claims Cheung. “Impact is virtually doubled. The question is: Can you do it?”

Capturing the centerline

Many martial artists understand the concept of the centerline, a principle emphasized in wing chun. As master Cheung define

s it, the centerline is the fastest line of entry between two opponents facing each other. The centerline concept is what differentiates wing chun from other systems of martial arts.

“In other styles, movement originates from outside toward the center. Other styles choose to use the curved line. Wing chun is different in that movement originates from the center outward. Wing chun is designed to cut the motions from other systems, and timing is the means to occupy the center first”‘ says Cheung. “It’s not wing chun if the movement doesn’t originate from the center.

“One must capture and control the centerline to occupy a superior position. To occupy the centerline in an instant is the mark of expert skill, by controlling it you have immediately developed a sense of what the opponent can or cannot do,” says Cheung. “You have, in essence, presented a question or problem for the opponent to answer.”

“Many wing chun men ignore the skill of closing the gap and distance fighting,” says Cheung. Wing chun’s famous motto explains, “Stay as he comes, follow as he retreats; rush in upon loss of contact.” To “rush in” means to overwhelm the opponent with a blast An analogy of the pressure of a river behind a dam suddenly opening its gates should help you understand this feeling of ‘rushing in.” Master Cheung continues, “Seeing a whole body charge at you has a totally different mental reaction the

n a fist coming at you. A fist is small, but an entire body is big. This mental shock can be unbalancing to my opponent”

Shocking the opponent

When you strike an opponent, you stun or shock him. The sh

ock causes a sudden overwhelming stimuli which can overload the brain and delay reaction. This shocking action allows you to setup your opponent for further consecutive strikes. Whether you choose to strike, yell, curse, spit or slap your opponent, the result is the same if you are successful. Your shocking blow will delay the reaction time of your opponent, causing an opening. if you hit him again, it canes more shock; more shock will cause more delay; more delay in reaction will cause more strikes to land. As Cheung says, “My fists are like drumsticks beating on a drum.” But he cautions, ‘Don’t let the shock reverberate back to you, as you will delay your own timing. Only through correct muscle conditioning and relaxation will you break the vibration back to yourself”

One day Hawkins said to this writer, “Attack me, Robert, anyway you like.” I complied and prepared to attack. Just as I did, I suddenly felt stunned, and I had Hawkins’ fist in my face. He smiled. ‘”Did you feel the shook? Did your mind ‘blank out?”‘ I felt first-hand his skill on entering and setting me up. Hawkins did not rain punches on me, but had he, I doubt that my 6 feet, 185 pounds would be able to stop anything after shocking my system.

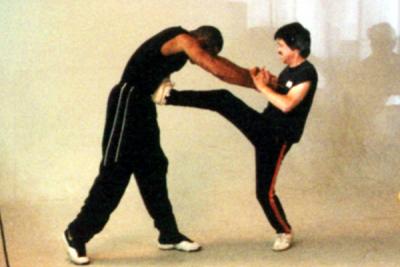

“To shock your opponent, you can use pak da (slapping strike), lop da or any other tool. You must catch your opponent with the correct tiling. When you shock your opponent, you cause him to blank out, and in that instance he loses himself and his surroundings, and there is an opportunity to destroy him!” says Cheung. “Anytime a martial artist, regardless of style, throws a punch or kick, he is blanking out because of the focus and emotional commitment” This blanking out gives you the time to strike your opponent.

The chi sao training is a famous feature of the wing chun system, but as master Cheung describes it, “Many wing chun practitioners overemphasize the drill. They find themselves unable to use the sticking hands in combat.” Cheung continues, “Sticking hands is for contact sensitivity. At long range and no contact with your opponent, you must have eye sensitivity. The problem with most wing chun practitioners is they have trapped themselves with only relying on contact sensitivity; you must have both. Both eyes sensitivity and contact sensitivity follow each other, where one leads off, the other follows to continue.”

“Chi Sao training is for you to get information on your opponent, but if you don’t have the contact and are at a distance, you must rely on your eyes. Master Cheung describes in detail that, “Eye sensitivity takes over when you don’t have the contact with your opponent; contact sensitivity takes over when you’re jammed up and or in close. If you don’t develop this, you win never he able to use wing chun.”

He cautions: “If a motion is too fast for the eye, it can be a trap, and if it is too fast for the hand, it may be a trap. In these circumstances, you must use your eyes to zoom in, or cut your opponent’s mo

tion by rushing in and use your contact sensitivity.” Master Cheung’s advice is reminiscent of a Patriot missile sighting a Scud missile in mid-air.

“What is important to learn is to control your opponent’s bridges and set him up for the next shot. Good wing chun is like playing billiards, you must always look for the next shot. Make your opponent follow you, if you are fast, make him catch up to you. If he is faster, make him slow. If he is hard, defeat him with soft. If he is soft, defeat him with hardness. If you can master the wing chun principles of ‘stay as he comes, follow as he retreats; rush in upon loss of contact,’ you win realize the essence of wing chun.”

Lien wan kuen: Consecutive strikes

After setting up the opponent with a shocking strike you must follow up with consecutive strikes. One of the most often drilled punches wing chun is called lien wan kuen. It is quick burst of straight line punches along the centerline that continues until an opponent is downed. Translated loosely in English, lien wan kuen means “chain punches” or “consecutive striking.”

“Lien wan kuen is a major application of the wing chun principle,” says Cheung, like an expert in billiards, each one of your shots scores and sets up for the next shot You do not give your opponent a chance to breathe. You strike and set up the opponent for more strikes until he is unconscious. You act like a butcher, cutting and hacking away at your opponent. Never stop until your opponent is down. That is the wing chun attitude.”

There is a certain amount of detached cruelty at work here. This aggressiveness has helped Hawkins survive many street encounters.

Trapping: Giving frustration

Trapping is the heart of wing chun. Sun Tzu wrote that all warfare is based upon deception, and to trap an opponent is to deceive him. Says Cheung, “When I trap your hand, your leg, or your body, your mind instantly freezes and considers the options. There is a psychological breakdown, and my opponent begins to lose his sense of confidence. When I don’t allow you the time to solve your immediate problem, I frustrate you, and therefore trap your emotions. You then have two opponents against you– me and yourself.

“If your opponent is fast, you be slow. If he is slow, you be fast. You must always keep in control of a fighting situation,” warns Cheung.

“If I can trick you, I am controlling your mid if I make believe there’s no pressure in my right hand, you may believe I’m not paying attention and want to attack there. But since I’m deceiving you, I want to draw your response so I can set up the next shot,” says Cheung.

An excellent example is the recent Persian Gulf War. Iraq’s strength was on the ground, but the Allied forces concentrated initially on air assault prior to any ground fighting. The tactic was to confuse the opponent and lead Iraq into concern of air assaults. Says Cheung, “You never allow your opponent to feel comfortable, that is the essence of trapping.”

Offense and defense

“Offense is based on attack, defense is based on body structure”‘ says Cheung. Offense is only 50 percent of the art Many wing chun men only concentrate on the offensive portion because offense is the best defense.” He warns, “Mastering the defensive portion of the art requires that one develop a strong stance and correct body structure. Defense means that you have to depend upon being a half-beat slower and follow your opponent and respond from there.”

For the wing chun practitioner, defense relies upon the correct structure of the body. The wing chun body structure holds back the rushing in of an opponent, much like a dam holding back a river. Again, we come to wing chun’s motto of “Stay as he comes, follow as he retreats; rush in upon loss of contact” Your body must stay and be able to receive your opponent’s rushing in.

Cheung describes the body structure as eating up the opponent’s space and his pressure. This is the soft part of the art Cheung again refers to the importance of the mind. “When an opponent rushes in toward you, you must have the mental preparation to receive the attack. Your mind must be calm.”

A wing chun principle is that the striking hand is the blocking hand. Offense requires superior timing in one beat A defensive counter works on a one-and-a half or second beat Wing chun’s simultaneous defense and offense is in one beat According to Cheung, “The best wing chun players can combine both offense and defense simultaneously in one beat if offense and defense are separate, you’re not adhering to wing chun principles. Many wing chun men don’t realize the importance of timing which makes the concepts come alive. You have to make the opponent blank out if you don’t make the opponent blank out, you have lost the superior one-beat timing. A common reason is because you have jammed up your own timing because the shock has reverberated to you. If a wing chun practitioner can master superior timing, he can be free from the style. if you master timing, the style is secondary. You can use the opponent’s technique at that point You have to train to reach that point It takes years of hard work; you literally gamble with timing.” There is a wing chun saying of “glass head, bean-curd body, and iron bridges.” Master Cheung is a living example of this expression. “Being physically small, I can’t take a punch or a kick,” says Cheung. “Using timing and these methods of attack, I never had to draw my last card” The last card that sifu Cheung speaks of is defense. Like the ground war during Operation Desert Storm, the last card is the trump card.

“If I had a body like Mike Tyson’s, I could afford to wait and play the defensive role and wait for my opponent,” says Cheung.

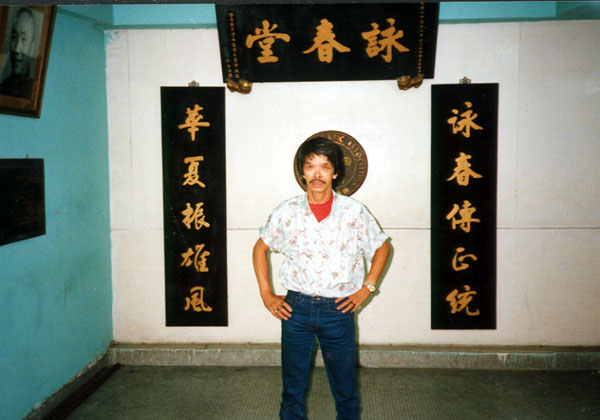

Forever Springtime The wing chun fist is named after its founder, Yim Wing Chun, but to Hawkins Cheung, the words “wing chun” also means “Forever Springtime”.

“If you look at wing chun this way, the art is always fresh and new.”

Sifu Cheung often explains that wing chun practiced in America has a different emphasis than in Hong Kong. “In Asia, we practiced wing chun to defend mainly against body blows, so you’ll have to emphasize crossing the bridge, gaun sao and other techniques,” he notes. “In America, you have boxers, wrestlers and other martial arts, each with their strengths, so you have to keep aware and adapt.”

Change and adaptation are essential to survival. That is why there are so many types of martial arts. He insists that like an immigrant, you have to change your ways to adapt to your new environment “A good wing chun player is a great pretender. He can adapt and change his tactics. You must change and adapt to circumstances to survive! That is the wing chun mind.

“Wing chun is a trap, too, because many practitioners get hung up thinking wing chun is the only way to fight. Many wing chun men are in the process of still developing the tools, so they can’t begin to conceptualize how to apply them properly in combat Changing to survive is universal, not just in wing chun,” says Cheung. “The frustrating part of wing chun is learning how to enter. This skill take years to develop.”

He concluded, “A master can only be a master today. You can’t tell what the future is, as the situation may change. You can only be a master up to the present An individual has to develop, continue with his own research and grow everyday.”

Wong Wah Bo and Leung Yee Tai had a student named Leung Jan. Leung studied the original art and later studied the art in set forms after they were choreographed by the Opera members. Leung became known for his application of Wing Chun in “Gong Sao” (Talking Hands a real match) and became known as the King of Wing Chun, or the Gong Sao Wong (Talking Hands King). Leung Jan has become the famous subject of books written by the famous fiction author Au Soy Jee and today, movies. It is known that Leung Jan became an herbalist and opened an herb stop on Chopsticks street in Fut Shan. The shop was called Jan Sang Tang (Mr. Jan’s Hall). Leung Jan was a native of Gu Lao, not Fut Shan. Leung Jan went on to teach a few, select students like his sons Leung Bik and Leung Chun, Chan Wah Shun, Muk Yan Wah, Chu Yuk Gwai, and Fung Wah.

Wong Wah Bo and Leung Yee Tai had a student named Leung Jan. Leung studied the original art and later studied the art in set forms after they were choreographed by the Opera members. Leung became known for his application of Wing Chun in “Gong Sao” (Talking Hands a real match) and became known as the King of Wing Chun, or the Gong Sao Wong (Talking Hands King). Leung Jan has become the famous subject of books written by the famous fiction author Au Soy Jee and today, movies. It is known that Leung Jan became an herbalist and opened an herb stop on Chopsticks street in Fut Shan. The shop was called Jan Sang Tang (Mr. Jan’s Hall). Leung Jan was a native of Gu Lao, not Fut Shan. Leung Jan went on to teach a few, select students like his sons Leung Bik and Leung Chun, Chan Wah Shun, Muk Yan Wah, Chu Yuk Gwai, and Fung Wah. The 40 points include classical and metaphorical names for each of the movements. In typical Chinese Cheng Wu style, this was designed so that members of other systems would not be able to understand what the movements were unless they had studied the same system. Some of these may indicate the Shaolin origin of some of the movements. Most of these names in modern Wing Chun have been replaced using modern jargon. Although few in number and perhaps not as intricate as the classical forms of Wing Chun, the forty points serve to review the Wing Chun system to the advanced practitioner, and serve as an excellent teaching tool to beginning students. They are trained in sets of repetition, alternating left and right sides. One should not simply look at the 40 points as techniques, but look at them as tactics to teach the fighting skills of Wing Chun. When the basics are mastered, a student can then look to doing combinations and permutations of the techniques while moving left and right, with high and low stances, or done high, middle or low levels, to the front and back, and while advancing and adjusting your steps. The advanced practitioner can reach the level of being able to change and vary his movements with empty hands or the double knives of Wing Chun.

The 40 points include classical and metaphorical names for each of the movements. In typical Chinese Cheng Wu style, this was designed so that members of other systems would not be able to understand what the movements were unless they had studied the same system. Some of these may indicate the Shaolin origin of some of the movements. Most of these names in modern Wing Chun have been replaced using modern jargon. Although few in number and perhaps not as intricate as the classical forms of Wing Chun, the forty points serve to review the Wing Chun system to the advanced practitioner, and serve as an excellent teaching tool to beginning students. They are trained in sets of repetition, alternating left and right sides. One should not simply look at the 40 points as techniques, but look at them as tactics to teach the fighting skills of Wing Chun. When the basics are mastered, a student can then look to doing combinations and permutations of the techniques while moving left and right, with high and low stances, or done high, middle or low levels, to the front and back, and while advancing and adjusting your steps. The advanced practitioner can reach the level of being able to change and vary his movements with empty hands or the double knives of Wing Chun. As with all Wing Chun systems, the Gu Lao 40 point system requires that the practitioner utilize the principle of “Lai Lou Hui Soong, Lut Sao Jik Chung”.

As with all Wing Chun systems, the Gu Lao 40 point system requires that the practitioner utilize the principle of “Lai Lou Hui Soong, Lut Sao Jik Chung”.